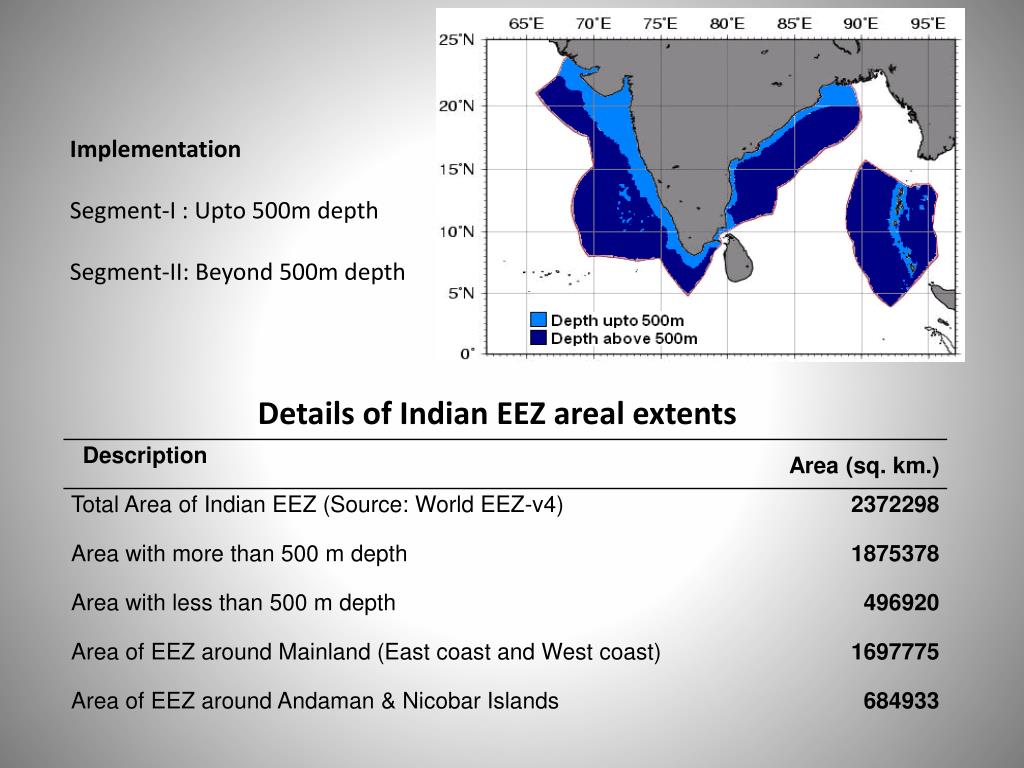

On November 26, 2008, ten terrorists entered Mumbai by boat, remaining unnoticed until they attacked and killed 166 people. This tragedy revealed serious weaknesses in India’s maritime security, a concern that is still relevant. India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), covering 2.3 million square kilometers, is crucial for economic growth, with fisheries generating $20 billion each year and untapped mineral reserves. However, this vast area faces increasing threats with illegal fishing costing billions annually, Chinese fishing vessels lurking around IMBL, smugglers exploiting border areas and Rohingya migrants trying to reach the Andaman Islands, raising both humanitarian and security issues..

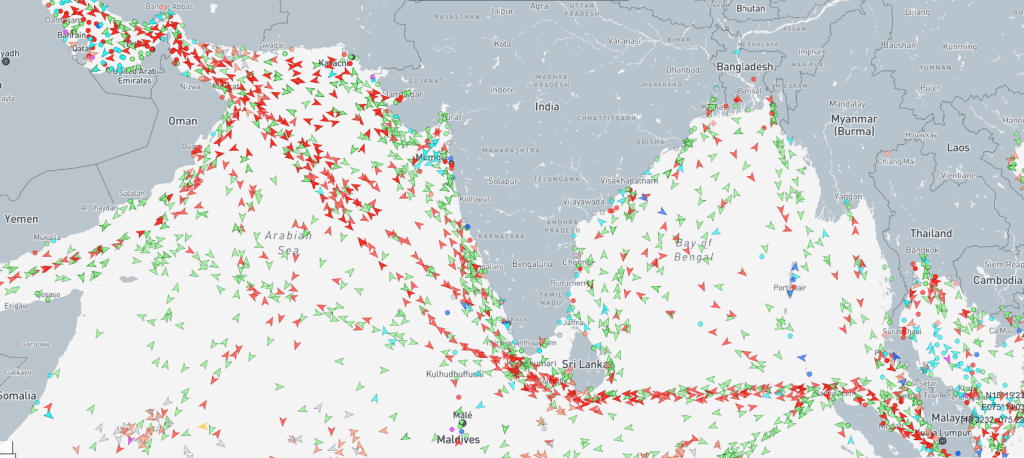

The primary agency involved here is Indian Coast Guard, responsible for securing this maritime frontier, facing a mission of growing complexity. With more than 150 patrol vessels and 70 aircraft, the ICG protects the entire EEZ providing Search and Rescue cover to much larger area, relying on Regional Operating Centre(ROC) and Remote Operating Station (ROS) along the coast, and Coastal Surveillance System radars at key ports. This limited capacity, stretched across tasks like intercepting smugglers, policing fishing grounds, and rescuing distressed mariners falls short of the ICG’s multi domain expansive duties. Where-in, human expertise shall focus on critical actions, such as boarding a suspicious vessel, and strategic decisions or like prioritizing cyclone response, the routine surveillance, vast and repetitive, should shift to advanced technology to ease the strain on effective workforce.

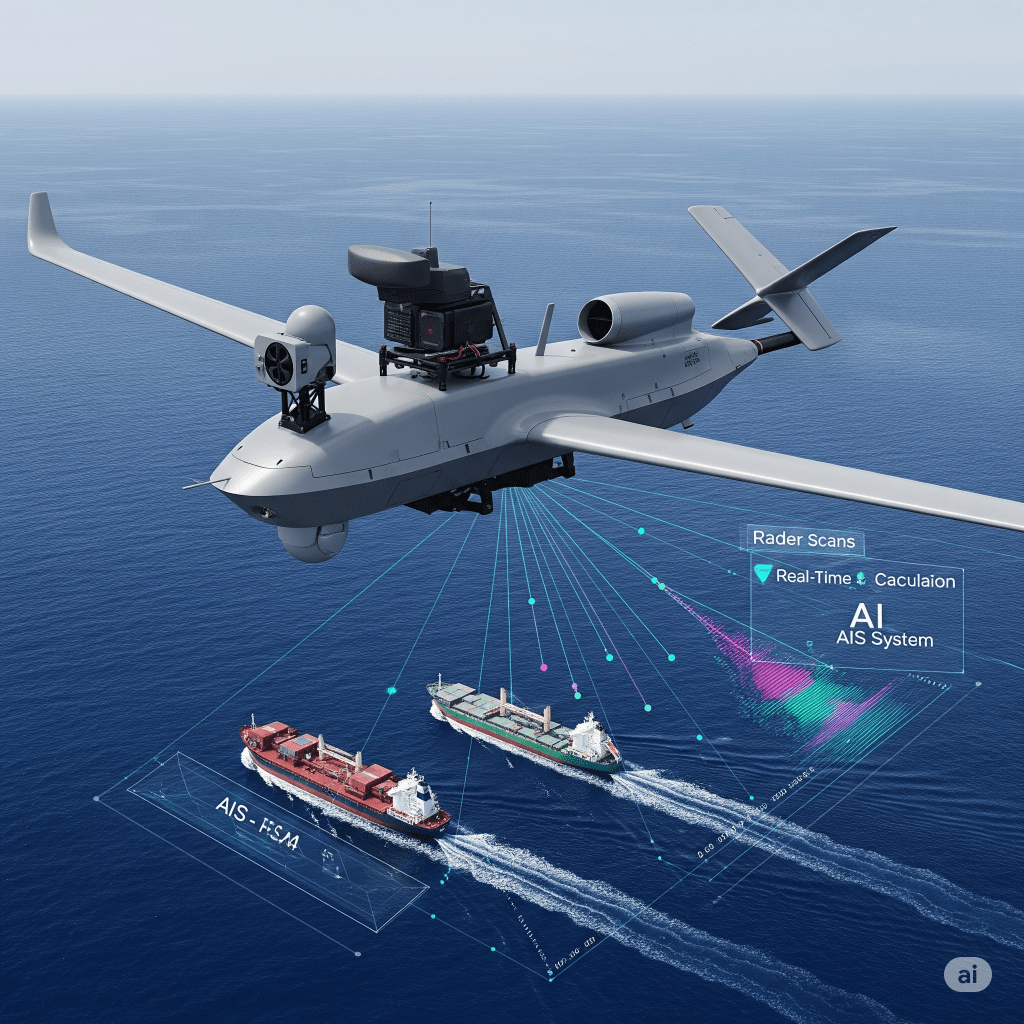

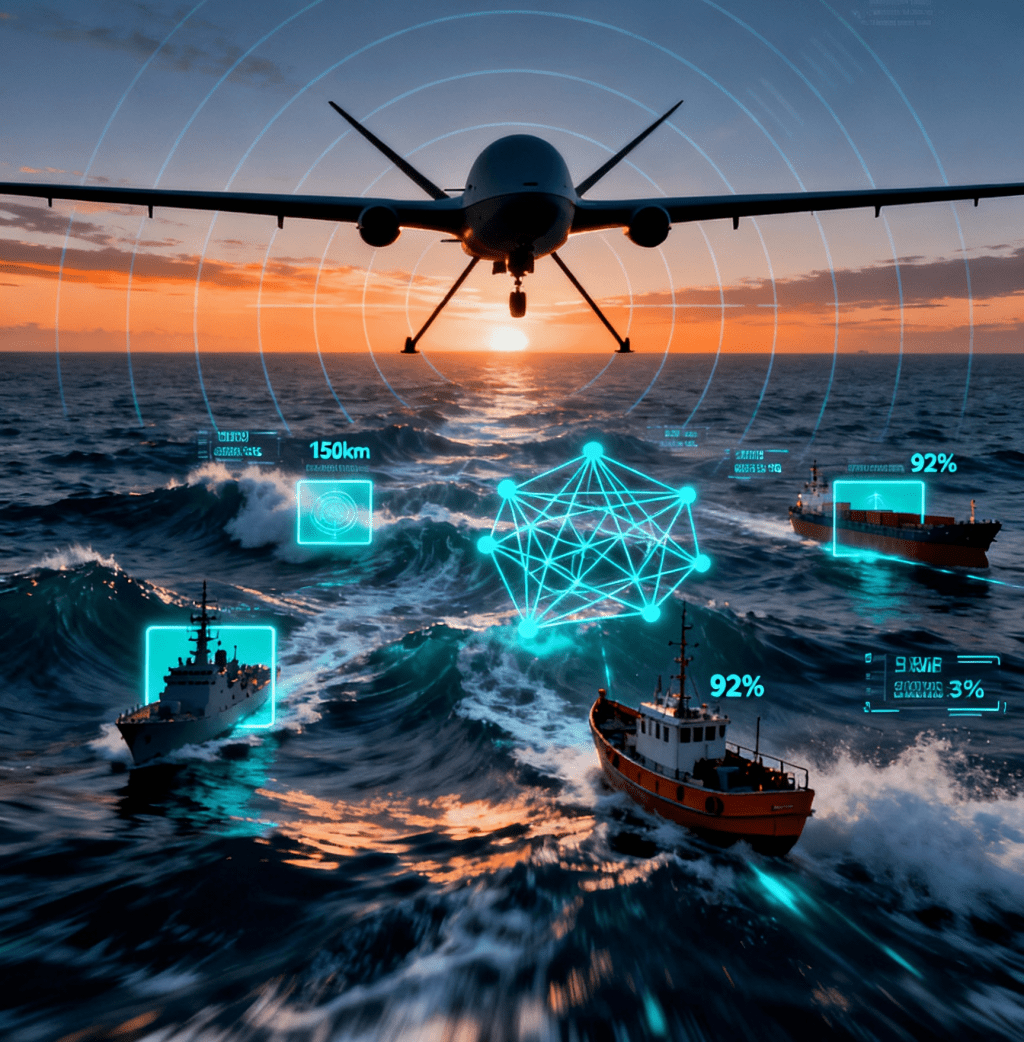

The most effective way to scan the oceans is through SAR equipped UAVs, which provide wide-area coverage, flying daily over threat-prone areas to pinpoint suspicious contacts in real time. Data from these platforms, processed by AI, identifies anomalies and flags behavioural patterns, such as a vessel disabling its AIS transponder and give direct actionable inputs to operations commanders.

The Maritime Threat Landscape

In December 2014, a Pakistani fishing boat laden with explosives was intercepted off Gujarat’s coast, only to self-destruct before the Indian Coast Guard (ICG) could board it. Suspected of planning a terrorist attack, the incident marked a persistent truth: India’s seas are as much a gateway to prosperity as a conduit for peril. The nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), spanning 2.3 million square kilometers and a coastline of 11,098 kilometers, supports fisheries worth billions annually and holds vast mineral reserves. Yet, this maritime domain faces a complex web of threats with environmental degradation, geopolitical rivalries, illegal fishing, and emboldened non-state actors, that demand robust surveillance. As these challenges evolve, the ICG’s mission to secure India’s waters grows ever more critical, necessitating advanced solutions to protect economic and security interests.

A Slow-Burning Crisis

Climate change is reshaping India’s EEZ, fueling security risks. Rising seas threaten to displace 1–2 million in West Bengal by 2030, while overfishing depletes fish stocks, costing the Bay of Bengal billions annually. Ocean acidification, up 30% since pre-industrial times, harms marine ecosystems. In May 2024, Cyclone Remal flooded the Sundarbans, displacing 100,000 and driving some to illegal fishing or smuggling, straining surveillance resources. These intensifying challenges demand advanced monitoring solutions.

Geopolitical Tensions

India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which touches seven countries Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Maldives, and Indonesia creates a geopolitical scenario that is much more complicated than its extensive 7,683-kilometer land border with six nations. Unlike the land borders that remain static and are monitored with fences and troops, the 11,098-kilometer International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL) is not fixed, it’s shaped by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which sets the rules for oceans and allows foreign vessels to have rights of innocent passage and navigation within the EEZ (United Nations, 1982). This complexity leads to disputes, such as Pakistan’s illegitimate claim over Sir Creek, where smuggling incidents are frequent, as well as issues in the Palk Strait, where Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing cases put a strain on India-Sri Lanka relations. The increasing presence of China, including unregistered vessels in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) in 2022, poses a challenge to India’s maritime supremacy, particularly around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Additionally, Bangladesh’s political instability started in 2024 raises concerns about migration risks in the Sundarbans. Unlike land borders, enforcing the IMBL requires a careful balance between national sovereignty and international obligations, necessitating real-time surveillance to prevent violations while adhering to global norms.

Eyes on Resource Raid by Chinese

Chinese distant-water fishing fleets, tracked at over 200 vessels around India’s EEZ in 2022 (to date, they don’t have courage to cross Indian EEZ), engage in Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing, threatening marine ecosystems near Indian waters. In African waters, similar Chinese IUU fishing has led to severe scenarios, devastating local economies and environments. In Ghana, Chinese-controlled trawlers have caused over millions of job losses among artisans fishers, while in Mozambique, depleted fish stocks have forced fishermen to spend entire days at sea for meager catches, exacerbating poverty and food insecurity. These activities, often obscured by disabled AIS transponders, mirror the challenges India faces.

Non-State Actors – Houthis and Beyond

Non-state actors are increasingly active in maritime security threats, with groups like Yemen’s Houthi rebels, Somali pirates, and China’s maritime militia displaying growing technical sophistication that inspires state-backed false flag operations. The Houthis, under Iranian support, have deployed drones, hypersonic missiles, and Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (UUVs), executing over 100 Red Sea attacks since 2023, including a notable claimed hypersonic missile strike in March 2025 (Al Jazeera, 2025). Somali pirates, operating with low-cost ingenuity, use GPS jammers and small boats valued under $10,000 to hijack vessels like the MV Ruen in 2023. Meanwhile, China’s maritime militia employs reinforced vessels and water cannons to assert dominance in the South China Sea, blurring civilian and military lines. States exploit these capabilities for false flag operations, covert missions under false flags, using non-state actors as proxies to disrupt rivals, challenging sovereignty or secure maritime chokepoints while evading accountability, amplifying the threat landscape.

Low-Cost Solutions by Non-State Actors

Non-state actors are harnessing low-cost Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) to challenge maritime security, their affordability and sophistication enabling disruptive operations that echo state-backed black flag tactics. These autonomous or remotely operated boats, often costing under $10,000, require minimal infrastructure and eliminate risks to human crews, making them ideal for groups like Yemen’s Houthi rebels, who have used USVs to attack Red Sea shipping since 2023. Equipped with radar, cameras, and occasionally explosives, USVs allow actors like Somali pirates to patrol or strike with precision, as seen in the 2023 MV Ruen hijacking . In India’s 2.3-million-square-kilometer EEZ, such vessels could evade traditional patrols, smuggling drugs or arms. Enhanced by AI for real-time threat detection or GPS jammers costing as little as $1,000, USVs amplify the reach of groups like trafficking cartels, who can exploit India’s waters. States, taking cues from these tactics, may back proxies for covert operations, masking their involvement. This growing threat demands advanced countermeasures, like AI-augmented UAVs with SAR and AIS, to detect and neutralize these agile, low-cost vessels.

Mass Migrations

Mass migration, driven by climate change and geopolitical unrest, poses a growing challenge to India’s EEZ, mirroring Europe’s struggles with illegal migration and its consequences. In Europe, irregular migration has reshaped demographics, with Germany hosting over 1 million refugees, mostly Syrians, since 2015, altering urban populations and fueling social tensions. Sweden’s Malmö saw its foreign-born population rise to 34% by 2020, driven by Middle Eastern and African migrants, sparking debates over integration. Tragically, Mediterranean crossings have led to mass loss of life, with over 29,500 migrant deaths since 2014, including the 2023 Adriana sinking, where 600 perished . India faces similar risks by 2030, as rising seas could displace 10–20 million Bangladeshis, pushing migrants toward the Sundarbans, where 78 were deported in 2024 . Rohingya boat crossings to the Andamans, posses a demographic shift challenge to Indian coastal population.

The UAV Solution

In 2024-25, high-risk fishing vessels surged in the Indian Ocean, with 100s of Chinese trawlers crossing the Malacca Strait, exploiting rising maritime traffic to mask illegal fishing. This gigantic maritime domain, spanning 2.3 million square kilometers and bordered by seven nations faces a complex landscape of threats.

TAPAS-Indigenous Drone

At the core of this system lies Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), a technology distinct from conventional radar. Unlike traditional radar, which relies on a fixed antenna and struggles in poor weather, SAR uses the motion to simulate a large antenna, achieving high-resolution imaging, down to 0.1 meters, regardless of clouds, rain, or darkness . Its features include all-weather functionality, wide-area coverage (up to 100 km swath), and the ability to detect small objects like vessels or debris. In maritime surveillance, SAR excels at mapping ship wakes, spotting oil spills, and identifying non-cooperative boats, even at night.

When paired with AI, SAR imagery is processed instantly, flagging anomalies like erratic vessel paths or disabled AIS signals, transforming raw data into actionable insights for human operators. The synergy of SAR and AI forms a robust maritime surveillance system. AIS transponders track vessel identities and positions, but smugglers often disable them to evade detection. SAR counters this by imaging vessels regardless of AIS status, while AI algorithms, such as YOLOv8, analyze imagery to detect unauthorized boats with 90% accuracy.

Thermal sensors, with resolutions like 640×512, identify heat signatures, crucial for locating migrants in distress during night operations. AI integrates these inputs, cross-referencing SAR, AIS, and thermal data to identify patterns, such as a vessel deviating from shipping lanes. This real-time analysis, powered by edge computing platforms like NVIDIA Jetson Orin, ensures low latency, enabling rapid human response.

This UAV solution minimizes operational overhead while maximizing impact. Technology SAR, AIS, thermal sensors scans the EEZ relentlessly, delivering clear, prioritized inputs. Humans, unburdened by routine surveillance, focus on execution: intercepting smugglers, rescuing migrants, or responding to piracy. As threats escalate from illegal fishing to climate-driven migration, this integrated system can ensure India’s EEZ remains secure, adapting indigenous innovation to protect maritime wealth and sovereignty efficiently.

The Force Multiplier in Maritime Surveillance

Artificial Intelligence (AI) isn’t magic it’s a powerful tool that amplifies maritime surveillance. By sifting through data from SAR and AIS like a tireless detective, AI delivers insights humans might miss. SAR’s high-resolution images, capturing vessels through clouds, are analyzed by algorithms like YOLOv8, spotting ships with 90% accuracy in seconds. AIS and S-AIS track vessel positions, but smugglers often spoof signals. AI cross-checks these with SAR, flagging mismatches instantly. Whether live during UAV flights or post-mission on high-speed processors, AI’s analytics maps, alerts, predictions equip user to counter threats efficiently, from illegal fishing to piracy.

Understanding the Core Technologies – SAR and AIS

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR)

SAR is an advanced radar system that uses the movement of its antenna (mounted on a UAV, satellite, or aircraft) to simulate a larger aperture, producing high-resolution images of the Earth’s surface. Unlike traditional radar, SAR excels in all weather conditions day or night, through clouds or rain making it ideal for maritime surveillance. It captures detailed imagery by emitting microwave signals and interpreting their reflections, enabling the detection of vessels, ship wakes, oil spills, or changes in ocean surfaces. The resolution can reach sub-meter levels, depending on the system’s frequency (e.g., X-band, C-band) and the platform’s altitude.

Automatic Identification System (AIS):

The Automatic Identification System (AIS) is a VHF radio-based tracking system mandated for vessels over 300 gross tonnage under international maritime law. It transmits real-time data, including a vessel’s identity (MMSI number), position (GPS coordinates), speed, course, and destination, at regular intervals typically every 2–10 seconds when underway. Traditionally, this data is collected by shore-based stations within VHF range, though unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with AIS receivers can also gather it in specific areas.

To extend coverage beyond terrestrial limits, particularly in remote oceanic regions, the Satellite-Automatic Identification System (S-AIS) was developed. S-AIS uses satellites to capture AIS signals globally, enhancing the ability to monitor vessel traffic in areas inaccessible to shore stations. Both AIS and S-AIS rely on vessels voluntarily broadcasting accurate information, rendering them susceptible to spoofing or intentional disabling by vessels attempting to evade detection. This vulnerability necessitates cross-verification with technologies like Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), which can visually detect vessels regardless of their AIS status, ensuring a more robust maritime surveillance system.

SAR Data Processing:

SAR produces complex imagery that AI analyzes using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) a type of deep learning model optimized for image recognition. CNNs can:

- Detect and Classify Objects: Identify vessels by their radar signatures, distinguishing between fishing boats, cargo ships, or military vessels based on size, shape, and wake patterns.

- Change Detection: Compare SAR images over time to spot new objects or environmental shifts, like oil slicks or illegal dumping.

- Mapping: Stitch multiple SAR images into high-resolution maritime maps, revealing activity in remote areas.

For example, a CNN might process a SAR image in real-time, identifying a vessel’s location and type within seconds, even in stormy conditions where optical sensors fail.

Data Analysis:

AIS generates time-series data, which AI processes using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or long short-term memory (LSTM) models—algorithms designed for sequential data. These models:

- Track Movements: Reconstruct vessel trajectories from AIS updates, calculating speed and heading.

- Behavioral Analysis: Learn typical patterns (e.g., shipping lanes, fishing routes) from historical data and flag deviations, like a vessel veering into a restricted zone.

- Anomaly Detection: Spot irregularities, such as sudden AIS signal loss, which indicate a vessel turning off its transponder to evade detection.

Data Fusion:

AI integrates SAR and AIS data for a fuller picture. AIS provides precise positional data, but SAR confirms it visually and detects non-AIS vessels (e.g., small boats or those with disabled transponders). A fusion algorithm might correlate a SAR-detected vessel with its AIS signal or flag it as suspicious if no AIS match exists.

AI-Powered Applications in Maritime Surveillance

AI’s ability to process and interpret SAR and AIS data powers four key capabilities:

1. Advisory Systems:

AI analyzes real-time and historical data to offer actionable recommendations. For instance:

- Suggesting optimal UAV patrol routes based on recent vessel activity.

- Highlighting high-risk areas (e.g., piracy zones or illegal fishing hotspots) for closer monitoring.

- Proposing responses to detected threats, like deploying coast guard assets.

2. Flagging Mechanisms:

AI automatically flags suspicious activities for human review, such as:

- Vessels entering no-go zones .

- Rendezvous at sea or zig zag movements, potentially indicating smuggling or illegal transfers.

- Patterns inconsistent with a vessel’s stated purpose (e.g., a “fishing boat” moving at cargo ship speeds).

3. Anomaly Detection:

AI excels at spotting outliers in large datasets:

- A vessel stopping unexpectedly in open water (possible distress or illegal activity).

- Erratic course changes deviating from normal shipping routes.

- AIS data contradicting SAR imagery (e.g., reported position doesn’t match visual detection).

4. Predictive Models:

Using historical trends, AI forecasts future scenarios:

- Predicting illegal fishing zones based on seasonal patterns and past violations.

- Estimating migrant boat routes by correlating weather, geopolitical events, and prior crossings.

- Anticipating traffic congestion in busy straits, aiding resource allocation.

From Data Collection to Analytics

Data collection occurs in two main phases during UAV operations. Firstly, during UAV sorties, the drones equipped with Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) payloads and Automatic Identification System (AIS) receivers gather data in real-time. The SAR scans the ocean surface while the AIS listens for VHF broadcasts. This data can be streamed to ground stations via satellite or radio links, such as 4G or 5G networks when within range, allowing for immediate analysis. Secondly, in situations with limited connectivity post-sortie, data is stored onboard, typically on solid-state drives, and is downloaded after the UAV returns. This approach enables deeper, non-time-sensitive analysis of the collected data.

AI-Powered PCs and GPUs

Processing SAR imagery and AIS streams demands significant computational power. AI-powered PCs with Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) are critical:

- Training Phase: GPUs accelerate the training of CNNs and RNNs on large datasets (e.g., thousands of SAR images or years of AIS records), optimizing model accuracy.

- Inference Phase: Once trained, these models run on GPUs to analyze new data in seconds or minutes, far outpacing human analysts

- For example, an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU can process hundreds of SAR images per minute, identifying vessels and anomalies with high precision.

Analytics Output:

Post-processing, AI delivers:

- Visualizations: Maps overlaying SAR-detected vessels with AIS tracks.

- Reports Summaries of flagged activities, anomalies, and predictions.

- Alerts: Real-time notifications for urgent threats, integrated into command systems.

Harnessing Next Technologies for Maritime Surveillance

Technologies like YOLOv8, Kpler, ICEYE, Sentinel satellite systems, and Windward, alongside deep search firms, are revolutionizing the way we take maritime surveillance globally. These tools fuse data from Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), Automatic Identification System (AIS), Satellite-AIS (S-AIS), and AI-driven analytics to deliver real-time insights, enabling rapid human response.

YOLOv8: Precision Object Detection

YOLOv8, developed by Ultralytics, is a state-of-the-art deep learning model for real-time object detection, excelling in processing SAR and optical imagery for maritime surveillance. Unlike traditional methods, YOLOv8’s anchor-free architecture and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) achieve high accuracy (up to 98% for ship detection) and speed (60–80 FPS on NVIDIA GPUs), identifying vessels, wakes, or debris in complex aquatic environments Its Global Attention Module enhances small object detection, critical for spotting non-AIS dhows or migrant boats. In maritime applications, YOLOv8 analyzes SAR imagery from UAVs or satellites, flagging anomalies like vessels disabling AIS.

Kpler:Trade and Vessel Analytics

Kpler provides AI-driven analytics for global maritime trade, tracking vessel movements and cargo flows using AIS, S-AIS, and satellite imagery. Its platform processes billions of data points daily, offering insights into commodity shipments, port congestion, and vessel behavior. Kpler’s machine learning models detect anomalies, such as vessels loitering near smuggling hotspots, by correlating AIS/S-AIS with trade patterns. In 2024, Kpler reported a 20% increase in tanker traffic through the Malacca Strait, highlighting its role in monitoring EEZ congestion.

ICEYE: SAR-Powered Persistent Monitoring

ICEYE, a Helsinki-based firm, operates the world’s largest constellation of SAR satellites, delivering sub-meter resolution (down to 25 cm) imagery day or night, regardless of weather. Unlike optical satellites, ICEYE’s SAR captures vast areas (up to 50,000 km² per image) and detects vessels against ocean backgrounds, ideal for spotting “dark ships” evading AIS. Its Ocean Vision product, launched in 2024, uses machine learning to analyze SAR data, identifying vessel presence, size, and location. A 2023 collaboration with Windward used ICEYE SAR to detect a covert ship-to-ship oil transfer in the Philippines’ EEZ, showcasing its investigative power .

Sentinel Satellites: Open-Source Earth Observation

The European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellites provide freely accessible SAR and optical imagery for maritime surveillance. Sentinel-1’s SAR, with 10-meter resolution, monitors vessel movements, sea ice, and oil spills, while Sentinel-2’s optical data (10-meter resolution) tracks coastal activities. In 2024, Sentinel-1 aided Vendée Globe sailors in navigating icy waters, demonstrating its reliability. Deep learning models, like Mask R-CNN, process Sentinel-2 imagery for ship detection, achieving high accuracy when paired with AIS data.

Windward: AI-Driven Maritime Intelligence

Windward, an Israeli firm, specializes in maritime AI, fusing AIS, S-AIS, SAR, and optical data to detect illicit activities. Its platform, powered by predictive models, analyzes vessel behavior, flagging anomalies like GNSS manipulation or dark pool activities. In 2024, Windward’s algorithms identified a 145% surge in high-risk fishing vessels in the Indian Ocean, aiding EEZ enforcement. A 2025 patent for detecting vessels sailing against currents enhanced its real-time GNSS spoofing detection. Windward’s integration with ICEYE SAR, as seen in the Philippines case, shows its fusion prowess. India could use Windward’s analytics to monitor smuggling in Palk Strait, leveraging AI to prioritize human response.

Deep Search Firms in Maritime Surveillance

Several firms lead in AI-driven maritime surveillance, complementing the above technologies:

exactEarth: A Canadian provider of S-AIS data, exactEarth tracks 250,000 vessels daily, integrating with SAR for global monitoring. Its analytics support IUU fishing detection.

Spire Global: Offers S-AIS and RF data, detecting 600,000 vessels monthly, with AI models predicting trafficking routes (Spire, 2024).

Starboard Maritime Intelligence: Uses SAR and AI to detect dark vessels, reporting a 30% increase in non-AIS ships in 2024. Starboard’s tools could bolster India’s piracy surveillance near Malacca Strait.

Technical Synergy and India’s EEZ

Despite India’s strategic dominance, with a 11,098-kilometer coastline and seven International Maritime Boundary Lines (IMBLs), the nation has leaned on imported maritime technology, with firms often assembling foreign spares. Yet, a transformative wave of government initiatives and startups like PierSight and Sagar Defence Engineering is reshaping this landscape, developing indigenous solutions to counter threat from IUU fishing losses, piracy spike in 2025, and climate-driven migration risks by 2030 . These efforts bolster AI-augmented UAV surveillance, integrating Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), Automatic Identification System (AIS), and Satellite-AIS (S-AIS) for India’s EEZ, ensuring technology delivers inputs and humans execute decisions efficiently.

Government Initiatives: Fueling UAV and AI Innovation

India’s government is driving maritime surveillance through targeted initiatives aligned with Atmanirbhar Bharat. The Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX), launched in 2018, funds startups with grants up to ₹1.5 crore (₹10 crore for iDEX Prime) to develop unmanned systems and AI analytics, with seven challenges awarded in 2024’s ADITI 3.0 (iDEX, 2025).

The Technology Development Fund (TDF) supports projects like underwater-launched UAVs, signing seven contracts in 2024 to advance ISR capabilities (Adda247, 2024).. These programs empower startups to build SAR-equipped UAVs and AI platforms, reducing reliance on imports, which accounted for 9.8% of global arms from 2019–2023. By fostering innovation, iDEX and TDF enable a lean surveillance system for India’s EEZ, addressing threats like smuggling and piracy.

PierSight: Satellite SAR for Wide-Area Surveillance

PierSight, founded by ex-ISRO scientists, is pioneering a SAR satellite constellation to enhance EEZ monitoring. Its Varuna demo, launched in December 2024 via ISRO’s PSLV-C60, achieved sub-meter resolution, detecting vessels and oil spills through clouds. PierSight’s 32-satellite plan, backed by $8 million in seed funding, targets persistent ocean intelligence by 2028, with $50 million in commercial commitments. In 2024, PierSight won the INDUS-X Maritime ISR Challenge, validating its SAR for UAV integration.

Sagar Defence Engineering: Unmanned Systems for Surface and Air

Sagar Defence, established in 2015, develops autonomous. Its Matangi USV completed a 600-km autonomous transit from Mumbai to Karwar in 2024, equipped with SAR and AIS for ISR. A 2024 TDF contract for an underwater-launched UAV (ULUAV) aims to deliver discreet surveillance, enhancing EEZ patrols. Operating from a 33,000-square-foot facility in Pune, Sagar Defence integrates AI analytics, supporting UAV data fusion for detecting dark vessels. Its USVs could relay surface data to UAVs, strengthening maritime security.

The Scale of the Challenge

India’s EEZ, the 18th largest globally at 2,305,143 km², extends 200 nautical miles from a coastline that includes 6,100 km on the mainland, 3,083.5 km in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Lakshadweep. With 12 major ports and 187 minor ports handling 75% of global maritime trade, and choke points like the Malacca Strait (60,000 vessels annually) and Strait of Hormuz (17 million barrels/day), the EEZ faces diverse threats with IUU fishing cases in Palk Strait, smuggling incidents in Sir Creek, and Houthi-related risks near the Gulf of Oman. The effective surveillance here requires ~460,000 km² daily coverage in high-threat zones, a scale that justifies a significant UAV fleet but allows for incremental progress.

A Modest Start:

| Type | Quantity | Endurance | Coverage per Sortie |

| Small UAV | 50 | 55 minutes | 500 km² |

| Medium-Altitude Long-Endurance (MALE) | 20 | 36 hours | 20,000 km² |

| High-Altitude Long-Endurance (HALE) | 3 | 30 hours | 50,000 km² |

AI Revolution for India’s Maritime Future

In 2024, a significant number of Chinese trawlers attempted to enter India’s 2.3-million-square-kilometer Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), contributing to a dramatic increase in high-risk vessels, which may lead to economic losses estimated between $1 to $2 billion due to illegal fishing activities. This alarming trend, combined with a rise in piracy incidents near the Malacca Strait projected for 2025 and mounting migration challenges, highlights an undeniable fact: proactive preparation for emerging maritime threats is not merely an option; it is an imperative necessity.

The nature of these threats is evolving. From AIS-spoofing by smugglers to sophisticated drone attacks inspired by groups like the Houthis, the risks faced by maritime security agencies are increasingly complex. Human operators, regardless of their training, are prone to errors and fatigue that cannot be mitigated solely by enhanced human performance. Consequently, even the most skilled personnel cannot rival the relentless accuracy and efficiency provided by AI-driven analytics.

Integrating advanced AI capabilities into India’s maritime surveillance and defense strategies ensures real-time monitoring, precise threat detection, and efficient response mechanisms. This technological evolution presents a unique opportunity for India to safeguard its maritime interests, promote sustainable economic development, and solidify its position as a global leader in maritime security. The necessity of embracing AI is clear, it signifies a commitment to build a resilient and secure maritime future.

Leave a comment