A new surveillance system promises to give military commanders the real-time maritime picture they’ve long been chasing but questions remain about cost, deployment speed, and whether rivals can catch up

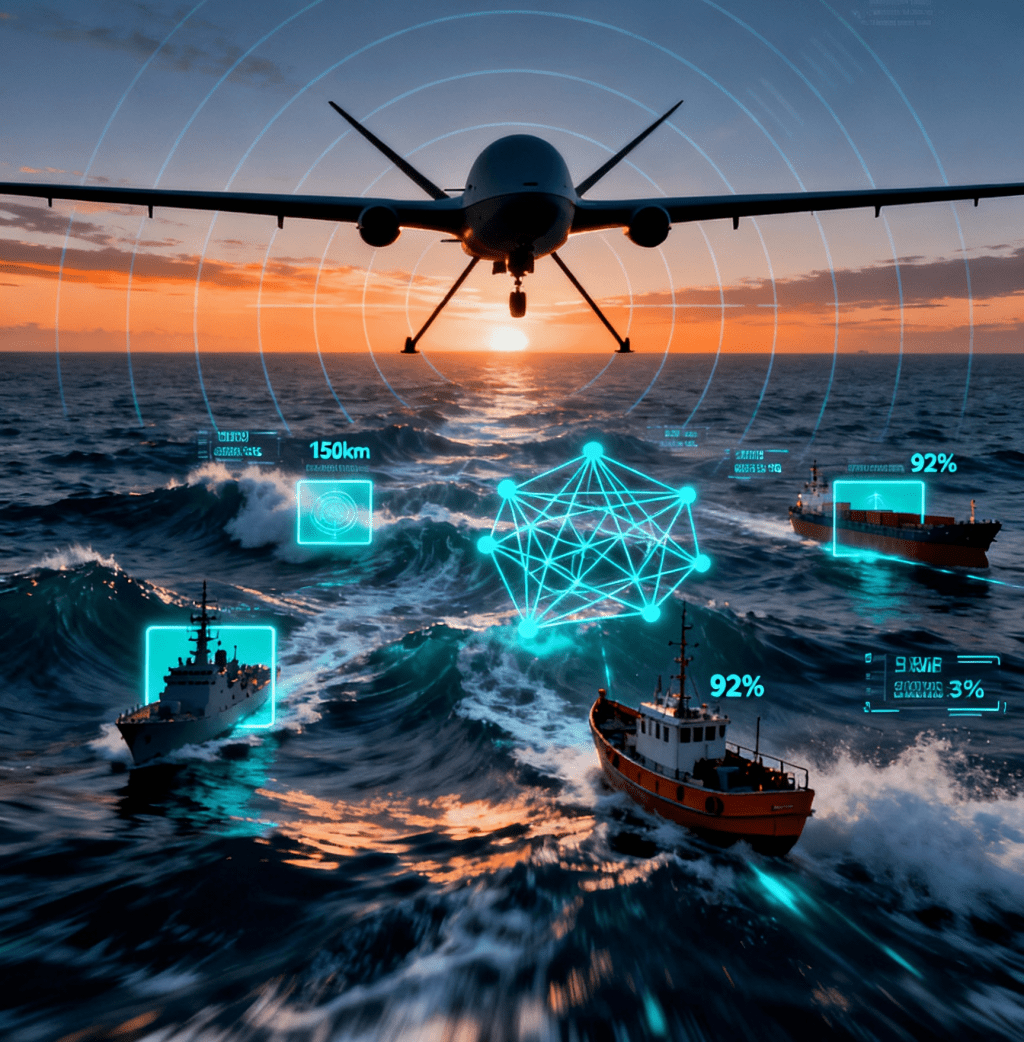

A radar system tested by Lockheed Martin over the summer demonstrated a capability that military strategists have pursued for decades: a machine that doesn’t just collect images of ships crossing the world’s oceans but understands what it sees and responds on its own. The system uses artificial intelligence to identify vessels in real time, distinguishing a warship from a fishing boat from a tanker, all without asking an operator or ground station what to do next. For a naval force trying to monitor vast stretches of ocean with limited resources, the implications are substantial.

The July 2025 flight test marked a turning point. The technology works. The challenge now is whether the U.S. military can field it quickly enough to matter, how much it will cost to deploy across the fleet, and whether other nations are already developing their own versions.

EIGHTY YEARS OF HARDWARE PROGRESS, ZERO PROGRESS ON THE CORE PROBLEM

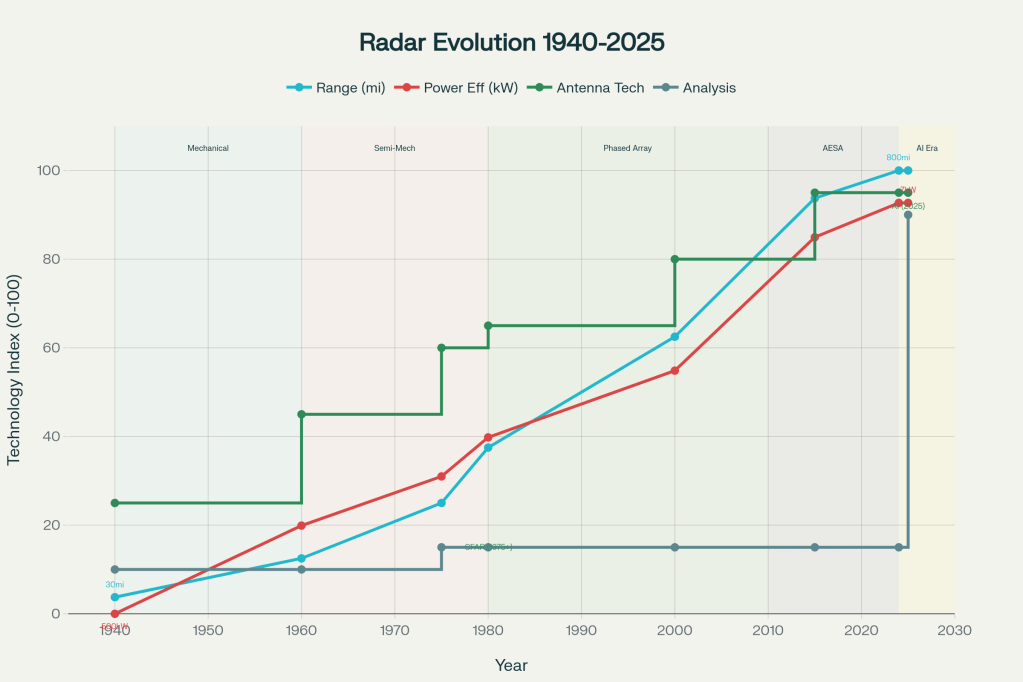

Radar technology has transformed almost beyond recognition in the eight decades since World War II. The first radar stations were massive fixed installations, their signals reaching perhaps thirty miles to detect approaching aircraft. Today’s systems see hundreds of miles. The old mechanical antennas that rotated in circles gave way to phased array systems that electronically steer beams in milliseconds. Power requirements dropped from megawatts to kilowatts to fractions of a watt. Resolution improved from detecting general cloud-like formations to identifying individual ships and distinguishing between vessel types.

Yet despite this extraordinary hardware progress, one fundamental problem remained almost entirely unsolved: figuring out whether what the radar was seeing was actually a target or just noise.

The challenge is older than the technology itself. A radar operator sitting in front of a screen sees a blip. Is that blip a warship? A fishing vessel? A container ship? Or is it a ghost signal created by how radio waves bounce off water? The operator had to make that call based on the appearance of the blip on the screen, its size, shape, how bright it appeared, whether it moved in a predictable pattern. Most radar operators trained for months or years to develop the intuition to make these judgments. Even then, they made mistakes.

The problem worsened as technology improved. Modern radars produce so much data that having humans analyze it all became impossible. Military strategists faced a paradox: the better their radar systems became at collecting information, the more bottlenecked their ability to use that information. They could not build fast enough to hire enough radar analysts to interpret the data flowing in. They could not train operators quickly enough to fill the seats. And the ones they did have were exhausted, working long watches where a moment of fatigue could mean missing a crucial target.

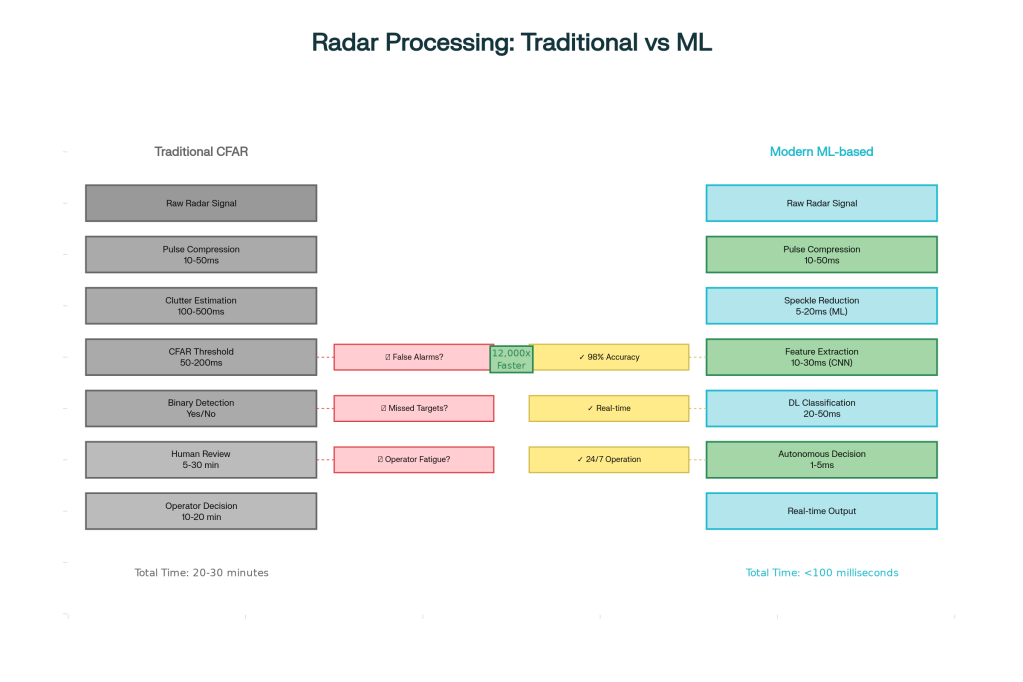

Radar engineers developed mathematical tools to help. They created algorithms like Constant False Alarm Rate detection, a method that adjusts sensitivity to maintain steady false alarm rates as conditions changed. But CFAR had limitations. It worked well in calm conditions but struggled in complex environments. In coastal waters where radar signals bounce off land features in unpredictable ways. In areas where multiple signals overlapped. In situations where the background clutter changed rapidly. CFAR could keep a fixed false alarm rate but often at the cost of missing real targets or producing floods of false alarms that made the system worse than useless.

The fundamental issue was that CFAR was built on mathematical theory without context. It could not understand that a slow-moving blip near a shipping lane probably meant a fishing vessel deliberately keeping radio silence. It could not learn that certain radar signatures belonged to military vessels and others to civilians. It could not distinguish between patterns that meant threats and patterns that meant routine commercial traffic. The algorithm had no framework for making those distinctions.

Every operational radar operator understood this limitation intimately. Managing gain, the sensitivity of the receiver. Adjusting signal processing filters. Ignoring certain radar returns that experience taught were always clutter. Focusing attention on areas where history suggested threats were most likely. These techniques worked but demanded constant human attention and judgment. The operator was the intelligent part of the system. The radar was just the sensor that fed him data.

This was the core problem that persisted from the 1940s through the 2010s: radar could collect information but not understand it.

THE PROBLEM THAT SPARKED THE SEARCH

Military surveillance of the ocean has always involved a contradiction. Radar can see through clouds and darkness, looking out dozens of miles in conditions where cameras fail. But for decades, what radar could see meant nothing without a person sitting in front of a screen, staring at patterns and making judgment calls. That operator might take twenty minutes or more to figure out whether a blip on the screen was a threat.

In maritime security operations, twenty minutes is a lifetime. Ships move. Threats appear and vanish. The window for responding closes fast.

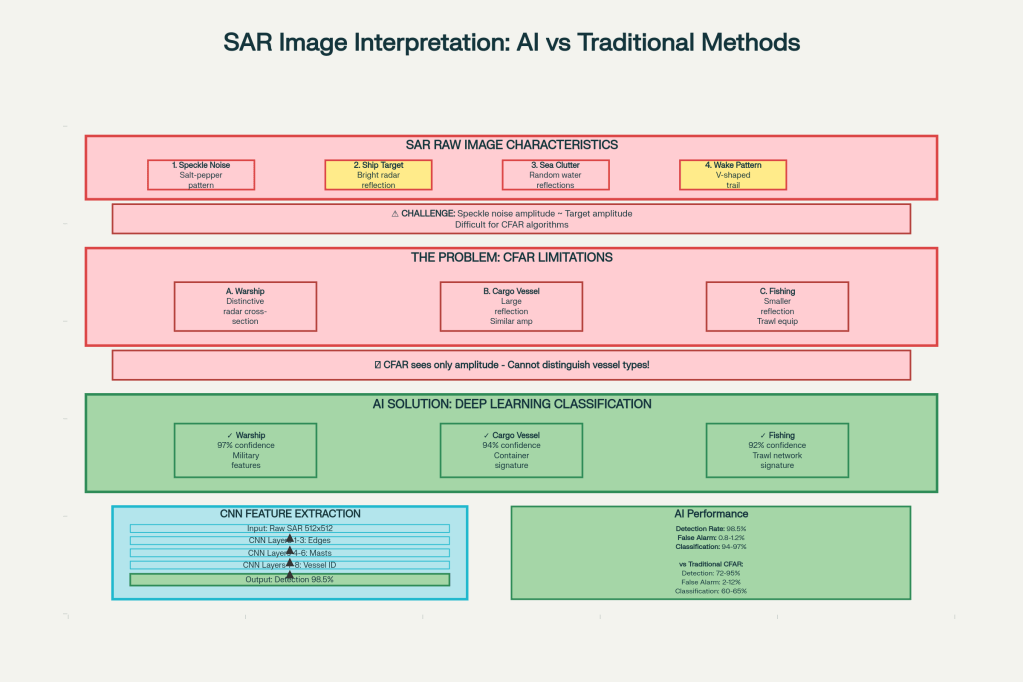

Operators also struggled with the core challenge of their job. Radar images look nothing like photographs. They require special training to interpret, and even experienced analysts made mistakes. A warship could look deceptively similar to a large cargo vessel depending on the angle and the radar’s frequency. Fog in the radar data, created by the physics of how radar reflects off water, could hide details or create false alarms. One specialist might see a threat where another saw nothing.

The human bottleneck became the limiting factor. As the volume of ocean that militaries needed to monitor grew, they hit a wall. They could not hire enough operators to analyze all the radar data flowing in from surveillance aircraft and satellites. Nor could they make operators work faster without exhausting them and inviting the very mistakes that expensive surveillance equipment was supposed to prevent.

THE TECHNOLOGY THAT CHANGED THE EQUATION

What Lockheed Martin and its partners built addresses this problem at its root. The system combines radar with machine learning algorithms that have learned to recognize ships the way humans recognize faces. The computer sees a radar signature and instantly knows what type of vessel produced it. It does not need to ask. It does not need to wait.

This breakthrough solves a problem that defeated traditional signal processing for decades. The old algorithms like CFAR worked by detecting signals above noise levels, but they could not distinguish between different types of signals. Machine learning approaches the problem differently. They examine thousands of examples of real radar signatures from different ship types and learn the patterns that distinguish them. A warship has a particular radar signature that looks different from a fishing vessel. Not always, but often enough that a system trained on many examples can make accurate judgments.

The system runs on specialized computer chips installed in aircraft or aboard ships. This is important. It means surveillance data doesn’t have to travel back to ground stations for analysis. The machine thinks about what it sees right there, where the radar is, and transmits only the meaningful results. For military operations where communications can be jammed or where sending large data files is impossible, this changes the tactical picture.

The underlying technology is not entirely new. Radar has been tracking ships since World War II. Machine learning has revolutionized image analysis across civilian industries for years. But combining the two required solving problems that academics had worked on for years without definitive answers. How do you train a machine to recognize ships when you have limited examples? How do you suppress the noise in radar data without losing the signals you need? How do you run these algorithms on hardware that weighs kilograms and consumes the power of a desk lamp rather than a locomotive?

Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works division took the lead. This unit has a history of solving impossible problems under time pressure. It designed the F-117 stealth fighter in classified secrecy and delivered the first prototype in half the time conventional programs would have required. The same philosophy that made that possible applied here. Small teams. Rapid decisions. Focus on solving the actual problem rather than following procedures.

The company brought together expertise from across its divisions. Radar specialists from the defense contractor’s sensors group. Machine learning researchers from its newly formed AI center. Weapons systems engineers who understand how the military actually works. All of them understood that the goal was not to publish a paper or win a grant. It was to build something that warfighters could use.

WHY LOCKHEED MARTIN, AND NOT SOMEONE ELSE

The breadth of skills required points to why Lockheed Martin stands alone in this space, at least for now. Developing this system required mastery of radar physics, which is a specialized field. It required expertise in machine learning and edge computing, which are relatively new skills but increasingly available in the tech industry. It required understanding military systems, operations, and how this tool would integrate into existing platforms. It required a secure facility where engineers could work with classified data and test against real tactical scenarios.

Few organizations meet all these criteria simultaneously. Raytheon Technologies and Northrop Grumman have substantial radar expertise. They are also large defense contractors with the resources to pursue programs like this. But they have not yet demonstrated systems with comparable capability. Northrop Grumman operates the Global Hawk reconnaissance platform with built-in SAR capabilities, which seems like an obvious place to add machine learning features. It has not announced such work publicly. Raytheon has invested in AI and maritime sensors but appears further behind.

Commercial companies working on artificial intelligence for maritime surveillance have impressive technical capabilities. Yet they work in open environments without access to classified military data or secure test ranges. Their systems might be advanced, but they are built to commercial standards and tested against academic datasets. Military systems must work under conditions where lives depend on reliability. The gulf between those two requirements is wider than many outsiders appreciate.

The international dimension matters too. U.S. government policy restricted access to high-resolution radar satellite imagery for many years. That policy is changing, but the historical effect gave American defense contractors practical experience that competitors did not have. Chinese and Russian defense companies are developing sophisticated radar systems, but they operate under intelligence constraints and export controls that limit opportunities to gather operational experience.

THE TECHNICAL CHALLENGE THAT NEARLY STOPPED THE PROGRAM

Building the software that recognizes ships in radar images proved harder than early planners expected. The fundamental problem was training data. Machine learning works by seeing thousands of examples. It learns the difference between a warship and a fishing vessel by studying thousands of radar signatures of both. But high-quality labeled radar imagery is rare. Creating it requires expensive collection flights, subject matter experts to annotate the images, and clearances to work with military data.

Lockheed Martin solved this through a combination of approaches. The company used radar imagery from declassified military collections where possible. It created synthetic data, using computers to simulate what radar would see reflecting off different ship types. It used data augmentation techniques that take limited examples and create variations by rotating and modifying them. And it employed a method called weak supervision, where engineers label the general area where a target is rather than marking its exact boundaries. This dramatically reduced the labeling burden while paradoxically producing better trained models.

The result was a system that works on edge hardware consuming minimal power. The system can process fifty radar images per second, the equivalent of what would have required a room full of operators a generation ago. The power consumption is measured in watts, not kilowatts. For an aircraft that might fly for hours or days, this matters.

THE EVOLUTION THAT ALMOST DIDN’T HAPPEN

Radar technologists often note a curious fact: during eight decades of radar history, the hardware evolved at breathtaking speed while the fundamental method of analyzing data barely changed. Each generation of radars represented enormous engineering achievements. The jump from mechanical antenna scanning to phased array technology happened in the 1950s. Operators no longer waited for the antenna to rotate. Beams could redirect electronically in microseconds. Detection ranges doubled then doubled again. Resolution improved from detecting general formations to identifying specific vessels.

Yet the operator in the seat in front of the screen was doing essentially the same job in 2020 as the operator had done in 1945. Staring at radar returns. Judging what looked real. What looked like clutter. What patterns suggested threats. Making calls based on experience and intuition. The tools had advanced but the method had not.

This gap mattered more as military challenges evolved. Cold War era radar operators faced a well-understood adversary with predictable tactics. They could learn what a Soviet submarine sounded like or what a MiG fighter looked like on radar. But contemporary maritime threats are more diverse. Piracy in African waters involves commercial fishing vessels deliberately disguising their identities. Illegal fishing fleets go dark to avoid detection. Smuggling operations use civilian vessels. Small fast craft can pose threats that conventional radar analysis struggles to characterize.

The old system of matching radar signatures to known threat patterns was breaking down. No single operator could build intuition about all possible maritime scenarios. No fixed algorithm could handle the complexity. What was needed was something that could learn continuously from new data and adapt to new patterns.

This is where the Lockheed Martin system represents a genuine break from the past. It addresses not an incremental improvement in radar hardware but a fundamental shift in how radar data is analyzed and understood. For the first time, the machine is intelligent about what it sees rather than just collecting data and leaving understanding to the human.

THE COSTS AND THE QUESTIONS

A complete system including radar hardware, processing equipment, and integration into a military platform would cost somewhere in the range of fifteen to twenty five million dollars according to defense industry analysis. That is not inexpensive. For comparison, the entire operating budget of a small nation’s navy might be less than that. But military decision-makers evaluate costs against capability. A single reconnaissance aircraft equipped with this system might replace several conventionally equipped platforms. Over a fleet’s lifetime, the cost-per-mission-hour becomes favorable.

The real uncertainty is production. Flight tests and small-scale operational trials are one thing. Scaling up to equip multiple platforms across multiple branches of the military takes years. Traditional defense acquisition timelines can stretch to five years or longer between successful testing and initial operational deployment. Lockheed Martin has indicated it wants to accelerate this, but whether the Pentagon’s bureaucracy will allow that remains unclear.

Cost per unit will likely drop if production ramps up. Defense contractors typically see ten to fifteen percent cost reductions for every doubling of production volume. But initial production quantities matter enormously. If the military orders a hundred systems, the unit cost stays high. If they order a thousand, economies of scale kick in. Currently, the signals are mixed. The system is impressive, but it has not yet translated into firm defense department commitments.

THE RIVALS AND THE CLOCK

Russia and China are almost certainly pursuing their own versions of intelligent radar systems. Russia has decades of expertise in military radar. China has substantial resources devoted to surveillance technology and the domestic manufacturing base to produce systems quickly. Neither has demonstrated a public breakthrough, but that absence of announcement does not mean absence of work.

The strategic consequence is a window of opportunity. If the United States can field this capability fleet-wide within the next three to five years, it maintains a decisive advantage. The longer the timeline stretches, the higher the probability that rivals will develop something comparable or that they will develop countermeasures specifically designed to defeat this technology. History shows that military advantages seldom remain exclusive for long.

THE FUNDAMENTAL SHIFT IN OPERATION

What makes this capability significant is not just speed but the shift in who makes decisions. For most of military history, machines collected information and humans decided what it meant. The radar lieutenant studied the screen and called in a report. The photo interpreter examined prints and wrote an assessment. This system turns that model on its head. The machine makes the preliminary judgment. A human reviews the result and validates it or corrects it. Over time, humans learn to trust the machine more completely.

This creates tactical advantages. Sensor tasking becomes nearly instantaneous. The radar can focus on targets of interest without waiting for a human operator to decide it is worth investigating. But it also raises questions about what happens when the machine is wrong. Radar can be spoofed. Ships can be disguised. The system might misclassify a target. In a shooting war, such mistakes have consequences.

Military planners are approaching this cautiously. Current doctrine maintains human approval for any action. But the pressure to move faster and make decisions in compressed timeframes never stops. Years from now, the boundaries between human decision-making and machine autonomy will likely shift in ways current military leaders are hesitant to fully acknowledge.

THE ROADMAP

Lockheed Martin’s public statements indicate plans to integrate data from multiple sensors with the radar system. Electro-optical cameras would provide visual context. Infrared sensors would detect heat signatures. Radio signal detectors would identify electronic emissions. The goal is creating a complete maritime picture where no single sensor provides definitive evidence but multiple sensors together create high confidence.

This expansion creates genuine strategic depth. A single sensor can be fooled or jammed. But an adversary would need to simultaneously fool radar, optical, infrared, and electronic detection methods to successfully hide from such a system. In practice, that becomes nearly impossible. The technology therefore creates a form of maritime transparency that changes the strategic balance.

THE CONSTRAINT NO ONE TALKS ABOUT

Export controls will limit which nations get this technology. The United States maintains strict rules about what military systems it shares. Close allies like the United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan will likely receive systems. NATO partners might get a version with some capabilities restricted. Everyone else will not get it. This technology will reinforce existing military alliances and potentially widen the gap between the most advanced militaries and the rest.

WHAT COMES NEXT

The most immediate question is whether the Pentagon will commit to production contracts in 2026. That would signal serious intent and begin the clock on fleet-wide deployment. If production contracts do not materialize, the system remains impressive but marginal, a capability that might be deployed on a few platforms but never becomes a fundamental part of how the military operates.

The second question involves rivals. If Russia or China announce their own comparable systems within two years, the competitive dynamic changes. The advantage narrows. If they announce such systems within five years, the advantage dissipates further. The window for maintaining technical superiority is not indefinitely large.

A third question involves doctrine. How will the military adapt operations to trust a machine’s judgment about what it sees? Training and culture lag behind technology. Some older commanders may distrust the system. Some younger operators may trust it too much. Getting the balance right will take years of experience and will almost certainly involve some mistakes.

Finally, there is the human dimension. Radar analysis as a profession may not survive this technology. The jobs that existed for forty years filling operational positions with trained specialists may cease to exist. That transition will not be painless. Defense contractors and military planners generally avoid discussing the human cost of technological displacement.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

What Lockheed Martin built is not unique technology in the way the F-117 stealth fighter was unique. The underlying components exist in open source form. Academic researchers have published papers on similar architectures. Competitors have access to the same tools and techniques. What Lockheed Martin did was integrate these elements into a military system that works reliably under operational constraints. That is harder than it sounds and often more valuable than individual breakthroughs.

The broader implications extend beyond radar. This is one example of how artificial intelligence will reshape military operations. Sensors will become smarter. Weapons systems will become more autonomous. Command and control will shift from humans commanding machines toward humans collaborating with intelligent machines that sometimes take initiative. These changes are coming not because anyone planned them but because the technology works and the alternatives become obsolete.

The surveillance revolution Lockheed Martin has begun might eventually look like the radar revolution of World War II, when radar transformed naval warfare and air defense almost overnight. But this time the revolution will be different. It will not be about inventing new hardware. It will be about finally solving a problem that has plagued radar operators for eighty years. For the first time, the radar does not just see. It understands.

Leave a comment