Commercialization, Risk, and Governance in the Northern Sea Route Era

By early 2026, Arctic shipping has crossed a boundary that had resisted commercial logic for decades. The change is not best explained by melting ice alone. Ice conditions in the Arctic have fluctuated before, and experimental transits have occurred intermittently since the late twentieth century. What distinguishes the present moment is the alignment of commercial scheduling, multinational coordination, and institutional enforcement. Together, these factors indicate a transition from opportunistic passage to structured maritime activity.

The most visible signal of this shift is the entry of containerized shipping into Arctic planning. The announcement by NewNew Shipping Line of expanded Arctic container voyages into 2026 marks a qualitative change in risk posture. Container shipping is inherently intolerant of uncertainty. Unlike bulk or project cargo, containers embed time-sensitive supply chains, higher cargo liability, and stricter contractual penalties for delay or damage. When a container operator commits voyage slots “as ice conditions permit,” it is not testing feasibility; it is testing commercial reliability under constrained predictability. This move signals growing confidence not in Arctic safety, but in Arctic manageability.

Parallel to this development, the Northern Sea Route has begun to function less as a national experiment and more as a coordinated logistics corridor. Reports of joint trials, pilot charters, and synchronized planning by Russia, China, and partner states suggest a deliberate attempt to validate the route under real commercial conditions rather than symbolic transits. These trials are designed to answer practical questions, fuel behavior in prolonged cold operations, convoy coordination, escort availability, insurance exposure, and the integration of Arctic legs into broader intermodal supply chains. The emphasis is no longer on whether the route can be transited, but on whether it can be priced, insured, and scheduled.

This evolution has direct operational consequences. Routing decisions now involve balancing distance reduction against heightened uncertainty in speed, escort dependency, and environmental exposure. Fuel planning must account for cold-flow properties, viscosity management, and auxiliary system resilience. Risk management frameworks must assume limited salvage capability, delayed emergency response, and heightened environmental liability. These are not theoretical concerns; they directly influence charter-party terms, insurance premiums, and crew selection.

A third, less visible but equally decisive factor is the hardening of regulatory and insurance expectations surrounding polar operations. While the Polar Code under the International Maritime Organization has been in force for years, enforcement dynamics are changing. Authorities and insurers are now pushing enhanced training standards, formal ice-navigation certification, and demonstrable emergency preparedness as preconditions for acceptable risk. In practice, this means that compliance is shifting from documentation-based approval to capability-based scrutiny. Insurance pricing and coverage limitations increasingly reflect crew competence, training depth, and operational readiness rather than vessel specifications alone.

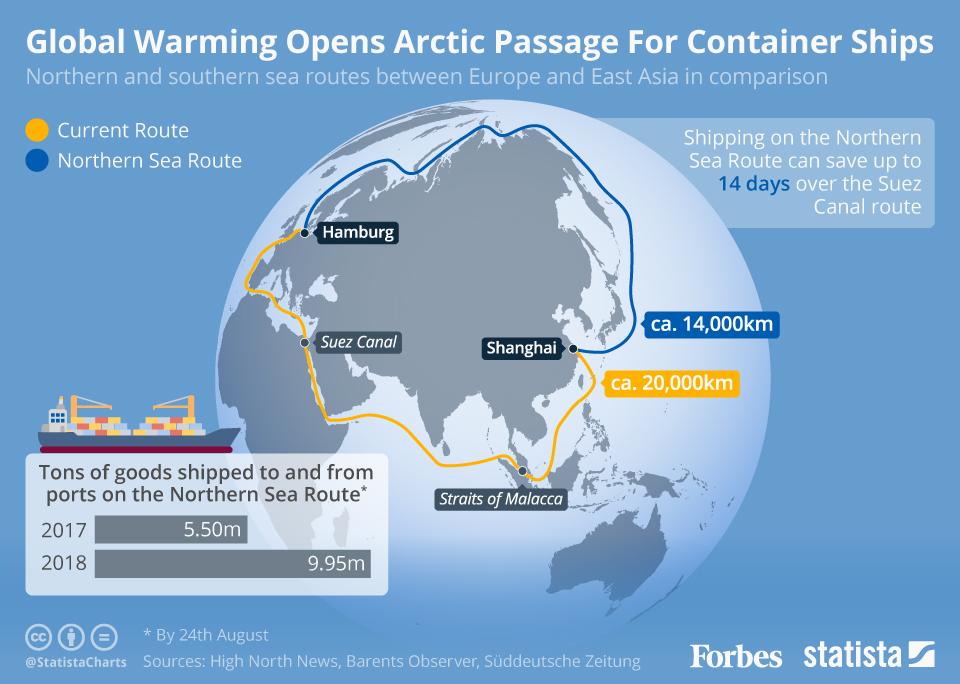

Taken together, these developments indicate that Arctic shipping in 2026 is entering a phase of controlled commercialization. The Arctic is not becoming a routine trade lane, nor is it replacing established routes such as Suez. Instead, it is emerging as a seasonal, state-influenced, high-governance corridor suited to operators capable of absorbing elevated risk in exchange for strategic flexibility. The commercial calculus has changed: success now depends less on exploiting shorter distances and more on mastering regulatory, human, and insurance constraints in one of the world’s most unforgiving operating environments.

This moment does not represent the normalization of Arctic shipping. It represents its institutionalization.

Why the Arctic Now?

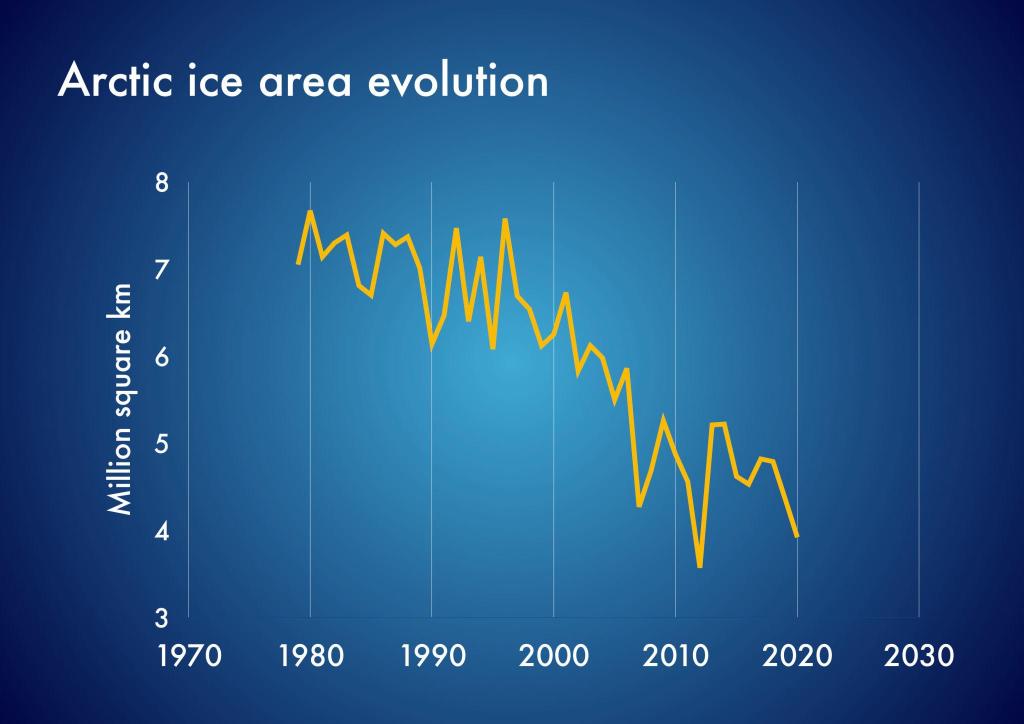

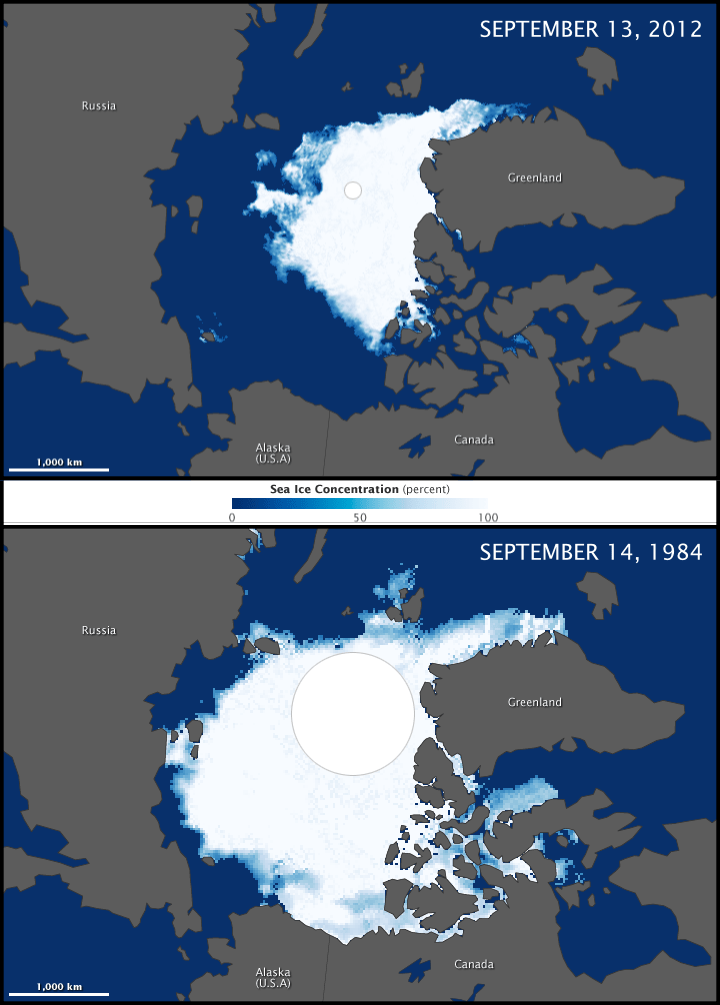

The renewed attention to Arctic shipping in the mid-2020s is often explained through a single variable: ice retreat. This explanation is convenient, visually persuasive, and fundamentally incomplete. Arctic sea ice has receded unevenly for decades, yet commercial shipping remained marginal, episodic, and largely symbolic. What has changed is not the physical environment alone, but the strategic environment in which Arctic navigation is evaluated.

At its core, the Arctic is becoming relevant because uncertainty once absolute is now bounded. Shipping does not require perfect conditions; it requires conditions that can be modeled, priced, and governed. Advances in seasonal ice forecasting, satellite observation, icebreaker coordination, and voyage data accumulation have not eliminated risk, but they have narrowed it into tolerable corridors. This transition from unknowable to probabilistic marks the threshold at which commercial actors begin to engage seriously.

Equally important is the changing nature of global maritime risk outside the Arctic. Traditional routes, particularly those transiting narrow chokepoints, have become strategically fragile. Congestion, geopolitical instability, sanctions regimes, and episodic disruption have increased the value of optionality in routing. In this context, Arctic passages are not pursued as replacements for established routes, but as strategic hedges alternatives that reduce dependence on single corridors rather than outperform them on cost or speed alone.

This reframing is critical. The Arctic does not compete with the Suez Canal on reliability, nor with the Cape route on predictability. Instead, it offers a different value proposition: seasonal access under sovereign control, with risks that are environmental rather than political or security-driven. For certain states and operators, this trade-off is increasingly acceptable.

Another decisive shift lies in how the Arctic is being conceptualized not as an open ocean shortcut, but as an intermodal system. Emerging Arctic shipping strategies emphasize integration with rail, riverine transport, and controlled port infrastructure. The sea leg is only one component of a broader logistics architecture designed to move goods across Eurasia with fewer geopolitical choke dependencies. This explains why container shipping, despite its sensitivity to delay, is now entering Arctic planning discussions. Containers signal not speed, but system integration.

Crucially, the Arctic’s growing relevance is inseparable from state involvement. Unlike traditional high seas routes, Arctic navigation remains deeply shaped by national jurisdiction, regulatory permissions, and infrastructure control. Icebreaker availability, pilotage requirements, port access, and emergency response capacity are all state-mediated. This has discouraged casual participation but favored operators aligned with national strategies or capable of operating within tightly governed frameworks. Commercial viability, therefore, is not merely a function of ship capability, but of political alignment and institutional access.

The Arctic, then, is not “opening” in the conventional sense. It is being structured. The conditions now attracting commercial interest are the result of deliberate governance, accumulated operational data, and shifting global risk perceptions. The question facing operators is no longer whether Arctic routes are possible, but whether they can be incorporated into long-term planning without destabilizing fleet economics, insurance coverage, and crew safety models.

Containerization as the Inflection Point in Arctic Shipping

For most of its modern history, Arctic shipping has been dominated by bulk commodities, energy cargoes, and specialized project movements. These cargo types tolerate delay, absorb schedule variability, and operate within bespoke contractual frameworks that already assume elevated risk. Container shipping does not. The entry of containerized services into Arctic planning therefore represents a decisive inflection point not because containers are new to cold regions, but because they fundamentally alter the risk calculus of Arctic operations.

The announcement by NewNew Shipping Line of expanded Arctic container sailings extending into 2026 illustrates this shift with unusual clarity. Unlike symbolic transits or one-off feasibility voyages, the planned program explicitly references multiple voyage slots, adjusted according to ice conditions. This language signals a move from demonstration to managed repetition. In commercial shipping terms, repetition is everything: it is what transforms a route from an experiment into a planning variable.

Containerization introduces a different operational discipline. Schedules become contractual obligations rather than aspirations. Cargo values are aggregated rather than discrete, amplifying liability exposure. Cold-induced damage condensation, packaging degradation, mechanical failure of reefer units moves from a peripheral concern to a systemic one. In this environment, even minor deviations in speed, routeing, or port access propagate rapidly through downstream supply chains. Arctic uncertainty, once acceptable at the margins, becomes central to commercial risk assessment.

The phrase “as ice conditions permit,” often used in Arctic shipping announcements, deserves careful interpretation in the context of container operations. It does not imply casual flexibility. Rather, it reflects an attempt to reconcile liner-style planning with probabilistic navigation windows. Ice conditions in the Arctic are not binary; they fluctuate in thickness, pressure, and distribution over short timescales. For a container operator, this means that schedules are no longer fixed timelines but risk-bounded windows, continuously adjusted through ice forecasts, escort availability, and real-time vessel performance data. The challenge lies not in navigating ice itself, but in synchronizing these adjustments with port slots, rail connections, and cargo delivery commitments.

Fleet implications follow directly. Ice-class requirements impose structural penalties in weight and hull form that reduce fuel efficiency in open water. Machinery systems must perform reliably during prolonged cold starts, low-load operations, and frequent speed changes induced by ice navigation. Redundancy often optimized out of conventional container vessels in the name of efficiency becomes non-negotiable. These factors increase capital expenditure while simultaneously constraining year-round utilization, creating a structural tension between Arctic capability and commercial return.

Yet it is precisely this tension that makes containerization such a powerful signal. Operators do not accept these penalties lightly. When a container line commits to Arctic deployment, it implies confidence that the route can be integrated into a broader network without destabilizing fleet economics. This confidence does not rest on the assumption of benign conditions; it rests on the belief that Arctic risk can be operationally governed through training, insurance alignment, state support, and disciplined voyage planning.

In this sense, containerization does not indicate that the Arctic has become safe. It indicates that it has become manageable. The distinction is critical. Safety implies stability; manageability implies control under constraint. The latter, not the former, is what enables commercial engagement in extreme environments.

The expansion of Arctic container services should therefore be read not as a triumph of technology over nature, but as evidence of a maturing risk culture. It marks the point at which Arctic shipping begins to interact with the most demanding segment of global maritime trade one where delay, damage, and deviation are measured not in days or miles, but in contractual penalties and reputational cost. That interaction will shape the future trajectory of Arctic routes far more decisively than ice charts alone.

The Northern Sea Route as a Coordinated Logistics System

The evolution of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) in the mid-2020s reflects a deeper structural change than a simple increase in vessel traffic. What is emerging is not merely a navigable passage, but a coordinated logistics system shaped by state oversight, controlled access, and deliberate operational sequencing. This distinction is central to understanding why recent activity along the NSR carries greater strategic weight than earlier Arctic transits.

Historically, Arctic voyages were framed as individual achievements, ships passing through ice under favorable conditions, often with significant escort support and bespoke planning. These voyages demonstrated possibility but not repeatability. The current phase, marked by coordinated trials and pilot charters involving multiple national actors, signals a transition toward system validation. The objective is no longer to prove that vessels can traverse the route, but to test whether the route can support predictable flows of cargo under defined governance and risk parameters.

Recent coordination among Russia, China, and partner states underscores this intent. Trial sailings are being structured to examine the full logistics chain: icebreaker availability and queuing, convoy formation, fuel consumption under ice-induced speed variability, communications reliability at high latitudes, and the integration of Arctic legs with rail and port infrastructure at either end. These trials are deliberately charter-based, allowing commercial exposure while insulating fleet owners from uncontrolled downside risk. The data generated rather than the tonnage moved, is the primary asset.

From an operational standpoint, this shift reframes routing decisions. The NSR is not being positioned as a permanent alternative to traditional global routes, but as a conditional corridor, activated when strategic, environmental, and political factors align. Distance savings are real but secondary. More consequential is the ability to reduce exposure to congested or politically volatile chokepoints, even at the cost of higher environmental and insurance risk. For certain cargoes and national strategies, this trade-off is increasingly rational.

Fuel and machinery considerations further illustrate the NSR’s system-level character. Prolonged operations in cold regions place sustained stress on auxiliary systems, fuel heating arrangements, and lubrication regimes. Speed variability imposed by ice conditions disrupts optimal engine loading, increasing wear and complicating fuel efficiency calculations. These factors cannot be managed voyage by voyage; they require systemic adaptation in maintenance planning, spare provisioning, and crew training. The NSR, in effect, demands a different operational philosophy from conventional trade routes.

Risk management along the NSR is equally systemic. Salvage options are limited, emergency response timelines are extended, and environmental sensitivity amplifies liability exposure. As a result, insurance acceptance hinges not on isolated compliance checks but on demonstrated integration across vessel ability, crew competence, and operational planning. Charter-party terms increasingly reflect this reality, incorporating clauses tied to ice conditions, escort availability, and state permissions. The route functions less like an open ocean and more like a regulated transit regime, where access and timing are negotiated rather than assumed.

Crucially, the NSR’s growing relevance is inseparable from state control. Icebreaker fleets, port infrastructure, pilotage services, and regulatory approvals are not market-neutral assets; they are instruments of policy. This does not negate commercial participation, but it conditions it. Operators engaging with the NSR must align commercial objectives with state frameworks, accepting that access, cost, and operational latitude may shift in response to broader strategic considerations.

In this context, the Northern Sea Route should be understood not as a shortcut carved by climate change, but as a constructed corridor, emerging through deliberate coordination, infrastructure investment, and regulatory enforcement. Its viability will depend less on average ice extent and more on the stability of the system that governs it. For shipping stakeholders, the implication is clear: participation in the NSR is not a navigational decision alone it is a commitment to operate within a tightly managed, politically inflected logistics architecture.

Regulatory Hardening and the Operational Reality of the Polar Code

For much of the past decade, the Polar Code occupied an ambiguous position in maritime governance. Formally adopted and universally acknowledged, it nevertheless functioned more as a compliance framework than as an operational gatekeeper. Documentation could be assembled, manuals drafted, and certificates issued without fundamentally altering how ships were crewed, trained, or operated. That phase is ending.

What distinguishes the current moment is not a revision of the Polar Code itself, but a shift in how it is enforced and interpreted. Regulatory authorities, classification societies, and most decisively, marine insurers are converging on a more exacting reading of what “polar-capable” actually means. Compliance is no longer assessed primarily through paperwork; it is increasingly judged through demonstrated capability.

This change is being driven less by regulatory activism and more by risk exposure. Arctic operations concentrate hazards that are rare in conventional trade: prolonged isolation, limited search-and-rescue reach, extreme environmental sensitivity, and constrained salvage options. A single incident carries disproportionate financial and reputational consequences. Insurers, facing asymmetric downside risk, have responded by tightening underwriting criteria. In effect, the Polar Code is becoming commercially binding, regardless of flag-state leniency.

The most visible manifestation of this shift is in crew training and certification. Generic bridge resource management and cold-weather familiarization are no longer sufficient. Enhanced ice navigation training, simulator-based scenario rehearsal, and documented emergency response competence are increasingly treated as prerequisites for acceptable risk. Importantly, this is not merely about technical skill. Polar navigation places unique cognitive and organizational demands on bridge teams: sustained vigilance in monotonous visual environments, rapid interpretation of ambiguous ice data, and decision-making under conditions where retreat may be as hazardous as advance. Regulators and insurers are beginning to recognize that these human factors are central failure points.

Operational preparedness has become the second major axis of scrutiny. Emergency response planning in polar waters cannot rely on assumptions drawn from temperate regions. Extended response timelines, limited external assistance, and harsh environmental conditions require vessels to function as largely self-contained systems during crises. This has elevated the importance of realistic drills, redundancy in critical systems, and clarity in onboard decision authority. Audits increasingly probe not whether a plan exists, but whether it has been stress-tested under polar assumptions.

The consequences of this regulatory hardening are already visible in commercial behavior. Insurance premiums for Arctic voyages are becoming more sensitive to qualitative factors such as crew composition, prior polar experience, and the operator’s incident history. Coverage exclusions related to ice damage, pollution, or delayed response are being refined. In some cases, insurers have effectively vetoed voyages by declining coverage where compliance is nominal rather than substantive. This dynamic has shifted power away from purely regulatory approval and toward market-based enforcement.

For operators, the implication is stark. Polar Code compliance can no longer be treated as a one-time certification exercise. It is evolving into an ongoing operational standard that must be continuously demonstrated. Investments in training, drills, and systems resilience are not discretionary enhancements; they are becoming the cost of entry into Arctic trade. Those unwilling or unable to internalize this reality will find that access to Arctic routes is constrained not by ice, but by the refusal of insurers and charterers to absorb unmanaged risk.

In this sense, the Polar Code’s true impact is only now being realized. It is transitioning from a regulatory baseline to a capability filter, separating symbolic Arctic participation from sustained commercial engagement. As Arctic shipping moves toward institutionalization, this regulatory hardening will shape who participates, under what conditions, and at what cost often more decisively than environmental factors themselves.

Human Factors and Crew Risk as the Dominant Failure Mode

As Arctic shipping moves from exceptional voyages to structured operations, the primary locus of risk shifts away from hull strength and propulsion power toward a less tangible, but more decisive domain: human performance. In polar waters, technology does not fail first; people do. This is not a criticism of crews, but a recognition of the cognitive and physiological strain imposed by an operating environment that remains fundamentally hostile to sustained maritime activity.

The Arctic imposes a set of human stressors that differ qualitatively from those encountered in conventional trade. Extreme cold degrades manual dexterity, slows reaction times, and increases fatigue even during routine tasks. Prolonged daylight in summer and extended darkness in shoulder seasons disrupt circadian rhythms, impairing alertness and judgment. Visual cues so critical to navigation are often ambiguous, with ice, water, and sky blending into a low-contrast field that defeats instinctive interpretation. These conditions erode situational awareness gradually, making error accumulation more likely than sudden failure.

Ice navigation, in particular, places unique demands on bridge teams. Unlike open-water navigation, where rules of the road and electronic aids dominate, ice navigation requires continuous interpretation of imperfect data. Radar returns are cluttered, satellite imagery may be delayed, and ice forecasts provide probabilities rather than certainties. Decisions about speed, heading, and whether to advance or retreat must often be made with incomplete information and without the possibility of external assistance. In such contexts, overconfidence in electronic systems can be as dangerous as their absence. The Arctic penalizes both hesitation and decisiveness when either is applied without contextual understanding.

Crew experience emerges as a critical differentiator, but experience itself is unevenly defined. Simulator-based training has improved markedly and is indispensable for introducing crews to polar scenarios. However, simulated competence does not always translate into real-world resilience. Ice behaves inconsistently; pressure ridges, brash ice, and leads evolve in ways that resist scripted scenarios. Crews without exposure to real ice conditions may struggle to recalibrate when textbook responses fail to produce expected outcomes. This gap between formal qualification and tacit knowledge is increasingly recognized by insurers and regulators as a latent risk.

Fatigue management represents another underappreciated vulnerability. Arctic operations often involve prolonged periods of heightened vigilance, punctuated by bursts of intense decision-making. Speed variability, escort coordination, and frequent course adjustments disrupt normal watchkeeping rhythms. In some cases, reduced speed extends voyage duration, compounding fatigue without the psychological relief associated with steady progress. The cumulative effect is decision degradation, where errors arise not from ignorance, but from exhaustion.

Organizational factors onboard further amplify these risks. Clear command authority is essential when operating in ice, yet hierarchical rigidity can suppress timely challenge and cross-checking. Conversely, overly flat decision structures can delay decisive action when conditions demand it. Effective Arctic bridge teams balance disciplined authority with active communication, a balance that must be deliberately cultivated rather than assumed. Training programs that focus solely on individual competence, without addressing team dynamics under polar stress, leave a critical vulnerability unaddressed.

From a commercial and regulatory perspective, these human factors are becoming increasingly visible. Incident analyses and near-miss reports from polar operations consistently point to judgment errors, misinterpretation of ice conditions, or fatigue-related lapses rather than structural or mechanical failure. Insurers have taken note. Crew composition, prior polar exposure, and demonstrated team training are now scrutinized alongside vessel specifications. In some cases, the absence of experienced ice navigators has been sufficient to render an otherwise compliant vessel commercially unacceptable.

The implication for Arctic shipping is clear and uncomfortable. Technical compliance and robust design are necessary, but they are not sufficient. The success or failure of Arctic operations will be decided primarily on the bridge, in the engine control room, and in the crew’s ability to sustain performance under prolonged stress and uncertainty. As Arctic routes become more institutionalized, the human element long treated as an abstract risk will increasingly function as the hard constraint on commercial expansion.

In this environment, investment in people is not a matter of corporate responsibility or regulatory goodwill; it is an operational imperative. Operators who underestimate the human dimension of Arctic risk may find that their most advanced vessels are rendered ineffective by the limits of crew endurance and judgment. Those who confront it directly will define the practical boundaries of Arctic shipping in the years ahead.

Leave a comment